Over the past 15 years or so, libraries around the world have de-emphasized cataloguing. While budgetary concerns and technological efficiencies have been factors in the decline of cataloguing, the emergence of full text search and relevance ranking as practiced by Google and others has proved to be more popular for the vast majority of users. On the open internet, subject classifications have proved to be useless in an environment rife with keyword spam and other search engine optimization techniques.

In the past year, the emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) with large language models with surprising abilities to summarize and classify texts has people speculating that AI will put most cataloguers out of work in the not-so-distant future.

I think that's not even wrong. But Roy Tennant will turn out to be almost right. MARC, the premier tool of cataloguers around the world, will live forever... as a million weights in generative pre-trained transformer. Let me explain...

The success or failure of modern AI depends on the construction of large statistical models with billions or even trillions of variables. These models are built from training data. The old adage about computers: "garbage in garbage out" is truer than ever. The models are really good at imitating the training data; so good that they can surprise the models' architects! Thus the growing need for good training data, and the increasing value of rich data sources.

Filings in recent lawsuits confirm the value of this training data. Getty Images is suing Stability AI for the use of Getty Images' material in AI training sets. But it's not just for the use of the images, which are copyrighted, but also for the use of trademarks and the detailed descriptions than accompany the data. Read paragraph 57 of the complaint:

Getty Images’ websites include both the images and corresponding detailed titles and captions and other metadata. Upon information and belief, the pairings of detailed text and images has been critical to successfully training the Stable Diffusion model to deliver relevant output in response to text prompts. If, for example, Stability AI ingested an image of a beach that was labeled “forest” and used that image-text pairing to train the model, the model would learn inaccurate information and be far less effective at generating desirable outputs in response to text prompts by Stability AI’s customers. Furthermore, in training the Stable Diffusion model, Stability AI has benefitted from Getty Images’ image-text pairs that are not only accurate, but detailed. For example, if Stability AI ingested a picture of Lake Oroville in California during a severe drought with a corresponding caption limited to just the word “lake,” it would learn that the image is of a lake, but not which lake or that the photograph was taken during a severe drought. If a Stable Diffusion user then entered a prompt for “California’s Lake Oroville during a severe drought” the output image might still be one of a lake, but it would be much less likely to be an image of Lake Oroville during a severe drought because the synthesis engine would not have the same level of control that allows it to deliver detailed and specific images in response to text prompts.

If you're reading this blog, you're probably thinking to yourself "THAT'S METADATA!"

Let's not forget the trademark part of the complaint:

In many cases, and as discussed further below, the output delivered by Stability AI includes a modified version of a Getty Images watermark, underscoring the clear link between the copyrighted images that Stability AI copied without permission and the output its model delivers. In the following example, the image on the left is another original, watermarked image copied by Stability AI and used to train its model and the watermarked image on the right is output delivered using the model:

If you're reading this blog, you're probably thinking to yourself "THAT'S PROVENANCE!"

So clearly, the kinds of data that libraries and archives have been producing for many years will still have value, but we need to start thinking about how the practice of cataloguing and similar activities will need to change in response to the new technologies. Existing library data will get repurposed as training data to create efficiencies in library workflows. Organizations with large, well-managed will extract windfalls, deserved or not.

If the utility of metadata work is shifting from feeding databases to training AI models, how does this affect the product of that work? Here's how I see it:

- Tighter coupling of metadata and content. Today's discovery systems are all about decoupling data from content - we talk about creating metadata surrogates for discovery of content. Surrogates are useless for AI training; a description of a cat is useless for training without an accompanying picture of the cat. This means that the existing decoupling of metadata work from content production is doomed. You might think that copyright considerations will drive metadata production into the hands of existing content producers, but more likely organizations that focus on production of integrated training data will emerge to license content and support the necessary metadata production.

- Tighter collaboration of machines and humans. Optical character recognition (OCR) is a good example of highly focused and evolved machine learning that can still be improved by human editors. The practice of database-focused cataloguing will be made more productive as cataloguers become editors of machine generated structured data. (As if they're not already doing that!)

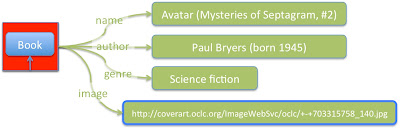

- Softer categorization. Discovery databases demand hard classifications. Fiction. Science. Textbooks. LC Subject Headings. AIs are much better at nuance, so the training data needs to include a lot more context. You can have a romantic novel of chemists and their textbooks, and an AI will be just fine with that, so long as you have enough description and context for the machine to assign lots of weights to many topic clusters.

- Emphasis on novelty. New concepts and things appear constantly; an AI will extrapolate unpredictably until it gets on-topic training data. AI-OCR might recognize a new emoji, but it might not.

- Emphasis on provenance. Reality is expensive, which is why I think for-profit organizations will have difficulty in the business of providing training data while Wikipedia will continue to succeed because it requires citations. Already the internet is awash in AI produced content that sounds real, but is just automated BS. Training data will get branded.

What gets me really excited though, is thinking about how a library of the future will interact with content. I expect users will interact with the library using a pre-trained language model, rather than via databases. Content will get added to the model using packages of statistical vectors, compiled by human-expert-assisted content processors. These human experts won't be called "cataloguers" any longer but rather "meaning advisors". Or maybe "biblio-epistemologists". The revenge of the cataloguers will be that because of the great responsibilities and breadth of expertise required, biblio-epistemologists will command salaries well exceeding the managers and programmers who will just take orders from well-trained AIs. Of course there will still be MARC records, generated by a special historical vector package guaranteed to only occasionally hallucinate.

Note: I started thinking about this after hearing a great talk (starting at about 30:00) by Michelle Wu at the Charleston Conference in November. (Kyle Courtney's talk was good, too).